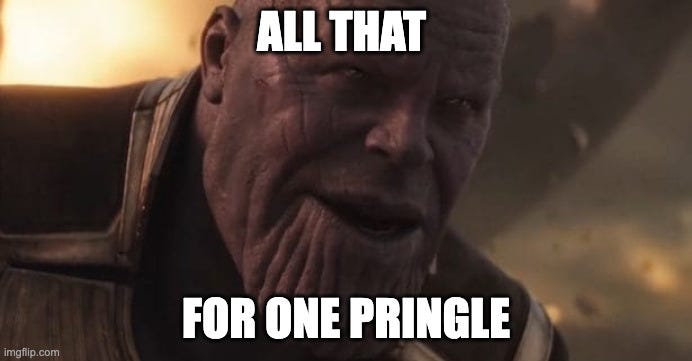

VoN #2: All that for one Pringle

In which AI has an energy deficit, Starmer has a values deficit, the Washington Post has an underpants gnomes deficit, and a Cochrane review of calorie counts on menus reveals a deficit... deficit.

I was going to do these every two weeks, but so much came up in the last few days that I couldn’t resist a bonus edition. Under promise and over deliver…. on which note, huge thanks to the over 700(!) people who’ve subscribed this month! It really means a lot, and it’s a big motivation to keep writing regularly. The next essay is coming on Tuesday and it’s a meaty one. Unlike…

Hey everyone, we’ve solved the obsesity crisis!

Calorie labels on menus and food packets encourage people to choose healthier options but only to the tune of 11 calories – the same as a single Pringle crisp.

My favourite Pringles fact is that the inventor of the Pringle, Fred Baur, had his ashes buried in a Pringles tube1. But back on topic: Cochrane have carried out a meta-analysis of studies on the impact of putting calorie counts on menus (confusingly the analysis includes a handful of studies from supermarkets as well). The results, considering the cost and effort of implementing the policy, are deeply underwhelming: a reduction of roughly 11 calories (one Pringle) per 600 calorie meal2.

What’s remarkable is the level of motivated reasoning coming from many of the academics quoted in the piece, who seem to view this as a thorough vindication of policy. For example, the review itself declares:

Current evidence suggests that calorie labelling of food … leads to small reductions in energy selected and purchased, with potentially meaningful impacts on population health when applied at scale.

Which… yes, sure, technically true I suppose; but it’s such a mealy-mouthed statement - ‘potentially meaningful’ you say! - that it’s empty of all meaning. A tiny amount per person ‘at scale’ is still a tiny amount per person. It’s not the kind of robust conclusion I would expect to justify the costs inflicted on low-margin businesses in a notoriously tough sector.

Nor does it justify the wider impacts of these policies, on all of us. I’m all for accurate labelling on groceries - it’s generally a good thing that we know what’s in the food we buy. But extending calorie counts to occasional social treats like restaurant meals or pub lunches feels like a sort of nationalised eating disorder, as if the very act of putting food into our mouths is somehow fraught with danger and must be obsessively monitored and controlled. There’s a soul-sucking joylessness in plastering warning metrics all over a nice meal out.3 But more than that: it feels profoundly unhealthy, and it’s no surprise that for people with eating disorders such measures may do more harm than good.

Every policy carries some social or economic cost, and in a sensible world we would consider repealing those which are ineffective once hard evidence like this - a gold-standard Cochrane review no less! - began to emerge. It’s a no-brainer: an easy way to reduce costs in a low-margin sector, keep legislature tidy, and demonstrate pro-growth, pro-business credentials with no harm or cost to anyone.

I await the inevitable review with baited breath…

Labour and the challenge of coherence (Sam Freedman)

A few lines in Sam’s summary of Labour’s position at the start of the new year stood out to me:

At the same time there’s frustration from senior officials and advisers that a lack of direction from Starmer makes it even harder to work this creaky machine. As I’ve noted before he doesn’t enjoy discussions about abstract philosophy or strategy; preferring concrete decisions on specific questions. In his first speech outside No. 10 he spoke of leading a government “unburdened by doctrine”. And, especially after the last decade or so, there’s a superficial attractiveness to a managerial leadership that isn’t demanding everything passes a rigid ideological test.

But you can’t run a country without some kind of guiding philosophy. The prime minister doesn’t have the time to be involved in every decision, which makes having clearly defined principles extremely important. They allow those around the PM to make decisions on his behalf confident that he will support them. Without that there simply isn’t the capacity for the centre of government to function.

The best leaders don’t make lots of decisions. In fact they go out of their way to not make decisions, because they understand that every time you have to make an on-the-spot decision you’re consuming organisational capacity and introducing some degree of risk4. The best leaders build a framework that makes most decisions automatic, preferably all the way down the organization. They articulate clear values and heuristics - “the customer is always right!” - and if they do a good job, then all the daily tactical choices flow from there, saving time and attention for the genuine head-scratchers.

Organisations that lack this framework tend to end up in decision paralysis, a phrase which is often a bit misleading. It’s rare that leaders can’t make decisions. More often they make too many decisions, pivoting decisively from one week to the next until they end up back where they started. Either way, the effect is the same: constantly changing your mind is the same as not making your mind up in the first place.

The result is slow, erratic and contradictory decision-making. You’ve probably experienced it at some point in your career. The same meeting seems to happen over and over again, discussing the same issues each week without resolution. Leaders squabble over trivialities as staff struggle to interpret the latest ‘weather’ from management. Instead of taking clear, consistent action, the business gets bogged down in constant debate, misalignment and frustration - “Why are we doing this?” - like a ship with one of its propellers pointed in the wrong direction.

In the absence of clear leadership, the culture that emerges is a sort of twisted mutant love-child of the strongest personalities. The flaws of the founders become manifest in the very fabric of the organisation. Uncertainty leads to insecurity which reduces trust. In low trust environments people fall back on short-term, defensive thinking. They skew away from the actual mission or long term health of the business, and focus on eking out small, short-term gains that will get them through the week, or advance their own, personal interests.

Still, you’re pretty unlikely to see that in politics, amiright?5

Underpants-Gnomesing the Washington Post

I’m going to leave aside the strategic genius of ‘make your customers happy’ and ‘earn more money’, insights which are sadly beyond my limited comprehension, and focus on the AI part here. In fact I’ll be even more generous, and leave aside the question of AI hype and whether this sort of technology can be effective at The Post.

My simple question is: what exactly is your competitive advantage here? All of your rivals have cheap access to exactly the same technology. At best this is a table stakes play, something you need to do just to keep pace with the competition. If you want to beat your rivals, you need to innovate - a better business model, a strategic partnership or acquisition that brings you some clear advantage in assets or technology, whatever - something that moves you into a different place on the board.

That’s something to bear in mind with any company whose plan for 2025-2030 is ‘embrace generative AI!’ Your reflexive answer should be: “So what? So is everyone else. What are you doing that’s different?”

Two reasons why Britain can’t compete on AI

Speaking of competitive advantage: my probably-dumb theory is that leadership on AI is less important than leadership on compute6, which requires leadership on energy. In the same way that exploiting the steam engine to its full potential required access to cheap steel, coal, rubber, transport, etc.; the latest generations of AI have vast requirement for things like chips and energy.

So Sizewell C and Hinkley Point C are perfect examples of the fundamental barriers we have to Keir Starmer’s goals on AI. We need nuclear power stations providing abundant energy to fuel the revolution, but ours are more expensive than in basically any other country on Earth, sometimes by orders of magnitude.

One of my favourite nerdy YouTube channels, B1M, has a deep dive into Hinkley Point C which includes the astonishing fact that due to UK regulation, the EDF-built station required a staggering 7,000 design modifications compared to an identical reactor built in France.

This means one of two things must be true: either the French are sitting on a time bomb, an unsafe power station that could go bang at any moment; or a lot of the design modifications - requiring vast amounts of additional steel and concrete (and therefore CO2 emissions) - are simply not necessary. It’s massively important that we know which option is correct: either tens of thousands of lives are at risk or billions of pounds are being wasted. Which is it, and is anyone even bothering to find out?

See you next Tuesday, in the meantime you can find me on BlueSky: https://bsky.app/profile/mjrobbins.bsky.social

I was going to say that it’s a great life goal to be buried inside one of your own inventions, but it probably depends on the invention and the circumstances. The inventor of the submarine was probably quite opposed to the idea during sea trials.

As a colleague once said of an over-priced starter at a pretentious restaurant, “I’ve farted more.”

I totally get that calorie counts can be useful for some people, and it’s nice that some restaurants provide them now, but I think there’s a high bar to get to ‘therefore this should be mandated by law’.

On a serious note, the same is true of lifestyle choices or dieting - your goal should be to remove as many decisions as possible, because making decisions in the moment is when you slip up. Ideally you want your choices to be such a habit that you’re not consciously deciding them, you just always grab this thing for dinner or go for a walk at this time. That’s why habits are so incredibly powerful.

Yeah, look at me with my profound political insights. Amiright?!

I may develop this thesis in a future post - if interested, let me know in the comments.

I never notice calorie counts of menus or takeaways. The traffic lights on packaged food are far more useful.