VoN #1: No bat death is acceptable.

In which we learn that one bat is worth 11-16 years of human life in Britain, that I once tortured James O'Malley in a desert, and the true meaning of 'Glorp'.

Welcome to Value of Nothing #1, a fortnightly-ish collection of links, facts and thoughts for your lazy Sunday reading pleasure. This week I tackle the big questions, such as: are bats better than humans, who is ‘Glorp’, and why is my car so damned expensive?

How to solve the £100m bat tunnel problem (Sam Dumitriu)

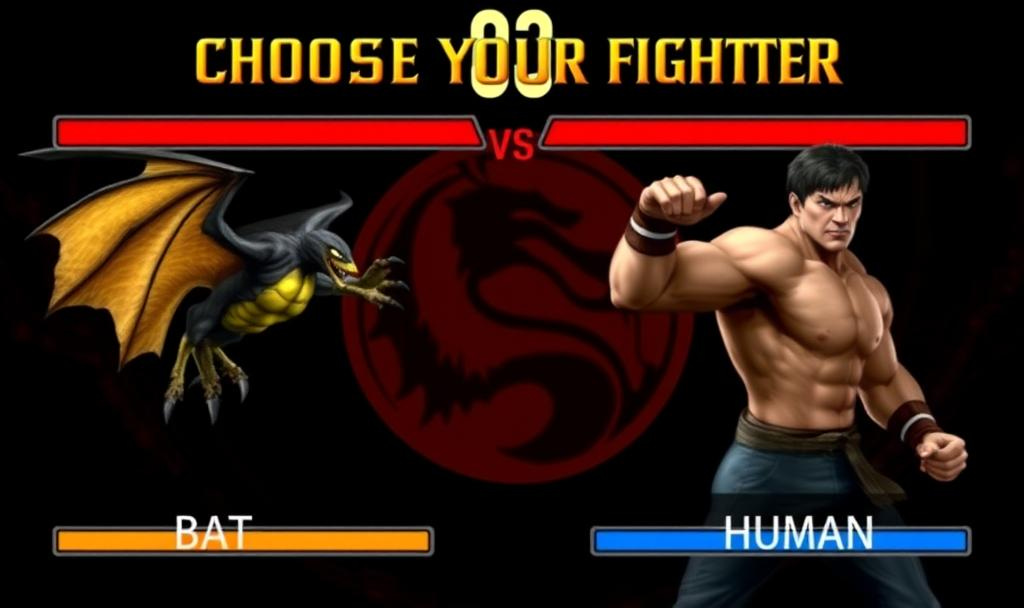

Which are worth more, bats or humans? Luckily, experts are on the case. Humans are covered by NICE, the National Institute for Health & Care Excellence, who regard £20-£30k per quality-adjusted year of life (QALY) as good value for a treatment. For bats we can turn to the good folk at HS2, who spent £100m on a tunnel to protect a colony of 300 of them, at a cost of roughly £330k per inconvenienced bat1.

If we adopt the bat as the standard SI unit of public spending (which we absolutely should), one QALY is worth around 60 to 90 millibats (mb). Or to flip that around: it is British government policy that one dead bat is worth roughly 11-16 years of human life.

Fine, yes, obviously it’s not British government policy; it’s an emergent value generated from a complex interplay between various state and non-state actors and the incentive structures they operate within. But that’s really the point: nobody intentionally decided that a bat was worth this much, it just sort of happened, and now it’s baked into the decision making of organisations spending billions of pounds.

Incredibly, there are people who think that number should be much higher. Natural England’s view was that: “no bat death is acceptable”. Functionally, that’s exactly the same as saying that the value of a bat is infinite. If no death is acceptable, then there is no possible threshold cost at which compromise can be reached. Indeed, most human development since the stone age, including frivolous activities like ‘agriculture’, should not have happened.

This is a kind of thought-terminating cliché, and it’s as bad for bats as it is for humans, because it discourages any interrogation of value. Is this the best use of £100m if you want to encourage bat populations? Almost certainly not, but value for money is irrelevant if your thinking starts and ends with the premise that the value of a bat is infinite and all compromise is immoral - we should simply spend the £100m, and then spend whatever else is required for any other measures.

That’s going to be a big theme of this Substack going forward: as a society, we’ve somehow ended up with institutional definitions of value that are wildly misaligned with each other, and in total opposition to goals like ‘raising people’s standard of living’. The costs of this are astronomical for our prosperity, our democracy, our future as a nation.

Luckily it’s not all bad news: to hear more about how people are working to stop situations like the bat tunnel in the future, check out Sam Dumitriu’s article, which is, if not optimistic, at least somewhat positive about the way forward, for bats, men, and batmen alike.

(Many thanks to Evil Whippet for the headline)

The cheems mindset meets the NHS app

Plans for an upgraded NHS App to allow more patients in England to book treatments and appointments will be part of a package of measures unveiled by the government on Monday.” [BBC]

This is brilliant news, unless you’re the BMA:

But the chairman of the BMA council, Professor Phil Banfield, said the focus should be on patients most in need rather than a "wasteful obsession" with artificial targets.

He said there was a danger patients without access to tablets and smartphones would be alienated.

Of course you could say the same for literally any intervention that makes things better for a majority of people, at which point your position is essentially ‘improve nothing’. You see versions of this again and again and again, for example here’s Stephen Bush getting fed up with bullshit objections to transport improvements:

These are all examples of the ‘cheems mindset’, an idea developed at the (excellent, subscribe) Normielisation Substack, which describes a sort of reflexive ‘but it’s too difficult’ response to any sort of change or improvement. This doesn’t apply to all criticism of course, lots of objections to policy are valid and can be used to improve ideas. The difference is that people doing this aren’t trying to improve things or make things better, or they’d work constructively to address their concerns. It’s an instinctive, visceral, negative response to anybody doing anything.

We’re all prone to this at times of course, and if you’re still casting around for resolutions for 2025 you could do worse than challenging yourself to adopt a more ‘can-do’ attitude. That doesn’t mean blindly following every dumb idea put in front of you - that’s how we ended up with much of the modern tech industry after all - but starting from a place of ‘okay, let’s steel-man this idea and not automatically dismiss it’.

Britain’s car market is a disaster (Me)

Car prices have exploded in the last decade, but perhaps because driving is coded as a right-wing, Clarksonian sort of issue it seems to get very little attention in progressive circles despite having a massive impact on things like poverty, employment, access to education and health services and quality of life for the millions of us who live in places where public transport isn’t an attractive option (i.e. Notlondonshire):

More worryingly, Jennifer and millions like her feel poorer, like their standard of living is going backwards, and that’s a really bad and corrosive thing when it comes to things like ‘people feeling the country is well run’. To a large degree we measure our place in society by the things we can afford. Whether that’s a good thing or not is a philosophical debate for another time; what matters here is that millions of middle-class people are finding that their expectations are wrong, that they’re ‘poorer’ than they thought. Understandably that frightens them, makes them feel insecure, and erodes their trust in government.

The social justice case for self-driving cars (James O’Malley)

I once force-marched James O’Malley across several miles of desert2, telling him at regular intervals for at least two hours3 that we were ‘about 10 minutes from the end’, reassurance that was entirely bullshit but seemed like the best way to motivate him at the time4. In the same way that Lawrence of Arabia forged his theories on modern insurgent warfare under the hot sun of the Arabian peninsula, I like to imagine that the core tenets of O’Malleyism were conceived during the long march5 across the blistering pebbles6 of Dungeness. Indeed, the first words7 through his blistered lips once he regained the power of speech were “I’ve just had a great idea about postcodes.”

Somehow we remain good friends (and occasional travel buddies) to this day, and his deserved success on Substack has inspired my own effort here. His latest post is on self-driving cars, and touches on one of the few areas where we slightly disagree - artificial intelligence. James is closer to the ‘naive, wide-eyed optimist’ end of the spectrum while I’m more on the ‘head-in-the-sand cynic’ side of things.

But his broader point is spot on: if we can reduce the price of transport through innovations like self-driving cars, we could enter a world of ‘abundant mobility’, a concept that currently exists only for rich tourists in developing world cities, where the cost of movement is essentially marginal. The consequences of this for our way of life could be incalculable, impacting the movement of people and goods in profound ways that change how we use services, how we socialise, where we live and what we do. It’s a fascinating read, about a goal most people seem to have given up on: abundance.

‘Answers by Glorp’

“Answers by Glorp” perfectly sums up the array of AI slop-features we seem to be faced with on a daily basis now. The question of course is why, given these services are often uneconomical to run given the huge costs of generative AI? It’s a theme I’ll likely come back to at some point, but I think there are three broad answers, one positive and two negative:

There are a lot of situations where this tech could genuinely be a holy grail for users, but the only way to improve it is to roll it out and get people using it so you can see how it performs in real world scenarios. This might be temporarily annoying to some users if not handled well, but it’s a positive approach.

Companies are desperate to show to investors and (in the case of B2B8 companies) enterprise clients that they’re on the generative AI wagon, so are stuffing features into their products to appease the market.

While most users just want to see the content they subscribe to in temporal order, this is anathema to B2C companies whose entire business model is predicated on manipulating feeds and directing people to profitable content. Generative AI allows them to build and control another layer of abstraction between what the user asks for and the actual content.

Products in the first category will hopefully improve over time. Products in the middle category will die out as they become too costly to maintain. Products in the third category will contribute to the continuing ‘enshittification’ of the internet. I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader to decide which of the products they use are in each category.

Anything I’ve missed? Anything you’d like me to write about? Leave a comment below. And please subscribe, because I’ve got a great piece about miserable children coming soon and you won’t want to miss their tiny, tear-stained faces.

Follow me on BlueSky | Twitter

It’s important to understand that these bats are not particularly endangered. We’re not spending £100m to prevent a species going extinct, we’re spending it to possibly protect 300 bats out of a population of tens of thousands. And in fact there’s little evidence the tunnel will actually achieve this.

Dungeness is sometimes described as Britain’s only desert, although a) technically it’s not a desert and b) I’ve been to Milton Keynes.

20 minutes.

Honestly it’s hard to tell as I stayed several dozen yards ahead for my own safety.

Two hours.

Luke-warm pebbles

After “F*** you, Martin, I’m never going on a walk with you again.”

B2B = Business to business companies or products, B2C = Business to consumer.

In a development which will come as no surprise to anyone, bats are also more valuable than women. Lighting is one of the key factors for women's safety at night, but in a straight fight between this and the needs of bats, the bats win. And there is loads of research on what kind of lighting they need and guidance and laws to follow. Research and guidance on lighting for women's safety? A big fat zero.

Yes, those were good links I wouldn’t have found on my own. Thank you