Son of bat tunnel

Bat infrastructure is springing up across the land, and Reform are on the case.

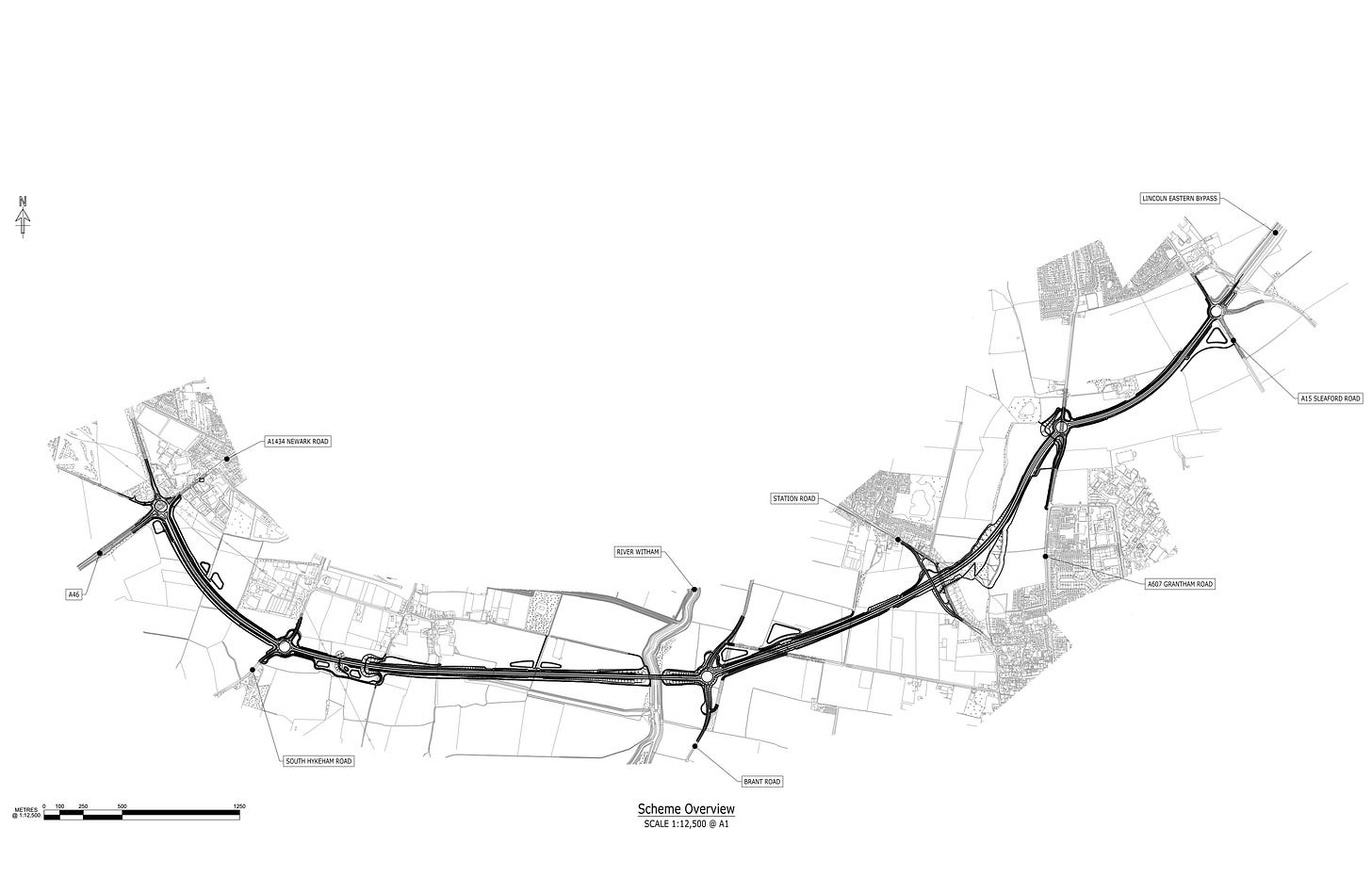

The North Hykeham Relief Road is a £200m project that will complete the last arc of a ring road around Lincoln, with massive benefits for the region. Like many infrastructure projects it is running over-budget, and with £75m of that cash being stumped up by Lincolnshire County Council, the new Reform leadership are asking hard questions. They’re right to, because some of these new costs are bewildering. In 2023 for example, Anglian Water said it would cost £3.1million to move affected pipes for the project. Just two years later they have upped that figured to a staggering £6.5million with little explanation. And then there’s the bat infrastructure.

According to the BBC: “A bat bridge costing £3m to build is now needed at South Hykeham and a bat tunnel costing £1.3m is required at Waddington.” That’s a cool £4.3m added to the budget, and to say these concepts were confusing to councillors is an understatement as you tell from this genuine, Pratchett-level exchange at a recent council meeting:

“How do you direct a bat through a tunnel?”

“Traffic lights?”

“You can’t put up a sign…”

“Bat language?

“No but they can’t see, can they.”

Leaving Britain’s finest minds aside for a moment, finding the origin of these requirements takes some unpicking. Councillors put the blame squarely on Natural England, per the BBC: “Lincolnshire County Council said it had been told by Natural England that it must build a bat bridge and a bat tunnel as part of the North Hykeham Relief Road project.”

But Natural England say they have nothing to do with it. "Natural England was not consulted on bat mitigation for the North Hykeham Relief Road and, as such, we did not require, 'demand' or design the bat 'culvert' and 'bridge' mitigation,” they told the BBC. “The proposals have been designed by the developers based on their own ecological surveys and legal obligations."

Except… you can find an extraordinary video on Facebook from Lincolnshire County Council’s Overview & Scrutiny Management Board, which questioned Sam Richards, the (apolitical) Head of Highways Infrastructure for the council. Richards clearly states that they approached Natural England to consult on bat infrastructure for the relief road, asking them what a ‘reasonable level of mitigation’ was. This would be a normal and desirable thing for any developer to do, so it’s hard to imagine why they’d lie about this, which makes Natural England’s statement completely baffling.

Richards and his colleagues were keen to consult Natural England because they were painfully aware of the disastrous sequence of events that led to a Norwich bypass being abandoned earlier this year after objections from the quango over… bats. The developers of that project had been in consultation with Natural England for the best part of four years when, according to the BBC, “the project's future was thrown into doubt, because Natural England changed rules protecting rare Barbastelle bats that live on the route of the proposed road.” The planning application had to be withdrawn in January, although it now seems to be moving forward again.

Surveys for the Lincolnshire project had found the same species, which is what eventually led to the addition of the South Hykeham Bat Bridge and the Somerton Gate Lane Bat Culvert to the North Hykham Relief Road, either with or without consultation with Natural England depending on whose account you choose to believe.

These aren’t quite as mad as the councillors imagined, and they don’t require bat signs or traffic lights. Hedgerows are important corridors for wildlife, and bats use their dark lines to navigate at night. If you interrupted the hedgerow with a gap for a dual carriageway, the bats would just plough into oncoming traffic; but if you continue the hedgerow over or under the road through a bridge or culvert the bats should hopefully follow that instead, which is better for bats, drivers and basically everyone except the guys that repair car windscreens.

But let’s rewind for a moment: how many bats are we talking about? In the same meeting you can hear the councillor asking about the bat survey that was performed. Pinning down the survey data was annoyingly difficult, but I found the environmental planning documents here, and eventually the bat surveys themselves, here. According to the former:

TEP undertook a Bat Survey in September and October 2022, which was updated in March 2023 – details of the Survey can be found in Ref: NHRR-TEP-EGN-HYKE-RP-LE-30013. Barbastelle bats were recorded across the site but not in all static monitoring locations, the survey concluded that barbastelles are utilizing the site at a sustained level in 2022 and 2023.

As far as I can make out, two types of survey were performed. Static surveys are where monitoring microphones are set up along suspected bat paths. Bats produce a constant stream of noise due to echolocation; and in the same way that you can tell the type of bird from its call, different bat species make distinctive patterns of noise which can be distinguished by machine learning.

This works fairly well, but it isn’t perfect. Nottinghamshire Bat Group point out that: “the success of automated bat detector deployment alone can be somewhat unpredictable for rare or cryptic bat species such as the barbastelle.” The Bat Conservation Trust publishes guidelines for professional bat surveyors which make a similar point. Barbastelle bats are unusually quiet and fast-moving, which makes them very hard for detectors to pick up. For that reason, it’s wise to back up the automated surveys with transects - people actually going out with bat detectors to try to spot the bats in person. In fact the gold standard would be to either catch one or find its droppings and do a DNA test.

Automated detectors were used at various points along the proposed road, and picked up the distinctive echolocation signals of Barbastelles at several locations; but the manual surveys led to only a single possible detection, by a road on the corner of a local industrial estate. It’s hard to know what to make of this - there are no roosting sites in the area, which is at the extreme north of the Barbastelle’s range, so this could be a handful of bats venturing into the fields to feed, or there could be far more than the detectors are able to spot. Indeed, as detection has advanced population estimates have been revised upwards - it may well be that they’re not as rare as we thought.

Either way, £4.3m of public spending has been allocated to protect an unknown number of Barbastelles on the say-so of a piece of software, backed up by a single human report. That’s a lot of cash, so you would hope that the measures are proven and reliable, but that’s not actually the case. Back in Norfolk again, which seems to be ground zero for England’s accidental war against the Barbastelle, similar bat protection measures were installed on the Norwich Northern Distributor Road at a cost of over £1m. A couple of years later, data on their effectiveness reached the BBC. It was not good: “none of the bridges was effective, with ecologists suggesting disturbance from the road may have driven the bats away.” A report issued by Norfolk County Council found that “just 13 bats crossed a £1.2m ‘green bridge’ during surveys.” Local populations of Barbastelles tagged with radio monitors had apparently just moved away.

That’s not surprising as Barbastelles are famously elusive, prefer woodland areas and avoid loud, bright, built-up environments. They are not fans of gentrification or major infrastructure projects. The most likely outcome of the North Hykeham Relief Road - a 70mph dual carriageway built across large open fields miles from any woodland - is that they simply feed elsewhere. If the goal was to help grow their population, the millions of pounds spent on bat bridges and culverts would have been better invested in new woodland habitats for them, away from major roads.

At this point I’m going to shock you and say that I think the ‘bat infrastructure’ should be built anyway. Not because of the Barbastelle bat but because protecting hedgerows is a Good Thing To Do. Green corridors are vital for all kinds of different wildlife, they’re essential to avoid the fragmentation of Britain’s ecosystems, and £4m on a £200m project is a rounding error given the environmental benefits. These are not £120m, kilometre-long, HS2-style bat tunnels, but a small bridge and culvert a few metres long.

What’s troubling is that we’ve built a crazy, Byzantine process for achieving this that lacks transparency, leaves local councils and developers in a state of fear and uncertainty, can block nationally-important projects for years on end… and probably doesn’t protect the bats anyway. If this is a good decision then we’ve arrived at it purely by accident, through an undemocratic and unaccountable process mediated by the whims of a quango, where even basic questions like ‘who recommended what to whom’ require Woodward and Bernstein to get on the case.

Once again, the behaviour of our institutions and the incomprehensibility of our bureaucracy is an absolute gift for populists. There is a reason Reform are drawing attention to this, and planning to raise the issue in Parliament: the playbook for 2029 is being written in these local skirmishes, with Reform positioning themselves as insurgents ready to tear down Britain’s bureaucracies, and it’s proving to be very effective.

I don’t think Natural England’s leadership understand how much danger their organisation is in, or realise that if Reform take power at the next election they could simply defund the quango and be done with it. As frustrating as Natural England can be in these situations, they exist for a reason. It’s good that we want to protect bats and wildlife when we build new infrastructure, and it’s great that we consider things like green corridors and hedgerows when we lay down new roads and railways. An over-correction that strips this out completely would be a very bad thing. It’s time to reform, or risk getting Reformed.

You can hear more on this story (and others), including some amazing audio from the council meetings on the topic, on our podcast.

Feels like some of these issues would be mitigated by having clearer standards around how roads are built. I.e a rule where major roads should have nature tunnels of a certain spec every X miles. Designs meeting the spec should be rubber stamped by planners without needing review by the relevant quango. Yes, it will add costs, but imagine the certainty and time reduction it would bring would outweigh that.

As an aside, I travel a lot in Germany and am often amazed at how standardised things like road junctions and train stations are. They seem to pick a design and mostly run with it. Something to learn from perhaps.

Such a good and nuanced piece. The key message to me is about speed - whatever decisions are made on planning rows we need them to happen faster.